is a “Substack Friend” whose writing I have found both edifying and challenging. At the end of April he published an essay, “Is Political Abstinence an Act of Privilege?” that satisfied both of those descriptions. Before my interaction and response I’d like to address some things, dear reader, in case you are not familiar with Caleb’s writing. Firstly, we come from different theological/ecclesiological traditions. This has an immediate impact on the topic at hand. I am a Confessional Presbyterian, my brother is from an Restorationist tradition. Nevertheless we are of the same substance, both being of one Lord, by one faith, in one baptism. My prayer then is that the both of us, and you too, are strengthened in our bond through the charitable interrogation of beliefs and ideas.

Second, do give his essay a read and subscribe to his Substack. At the end of last year I wrote a piece that included the exhortation to both writers and readers to make much of each others work in reading and sharing. I know I do not do all that I could, but I will not fail to implore you to visit and regularly read The Laymen.

Lastly, I was asked by the author himself if I would like to respond to his thoughts. I lunged at the opportunity. Dialogue and conversation is perhaps my favorite activity in the world and I am honored to be invited to so now. Caleb, I hope that one day, Lord willing, it will be in person!

The waters that Bratcher describes in the opening of his essay, I know well. I once swam in them. More than likely I was one of the sharks. Many details of the subsequently described assumptions I am familiar with because I was once blind to them. If his piece serves as a mirror, I see an old reflection. I am thankful for this essay, not as a point of pride at how I’ve ‘evolved’, but because I can take another look and make sure I haven’t gotten food in my teeth or that the zits haven’t returned again. They have a habit of doing that, you know.

A Brief Summary

As an abstainer from the formal political act of voting, Bratcher takes the interesting position of not defending the morality of his stance or taking lengths to make sure you know he is grateful for the right to vote. Instead he addresses the criticism of privilege - “must be nice to not vote and not worry, eh?”. In this reaction, not voting is not participating. Staying away from the ballot box means staying home with your feet kicked up. Not voting equals not taking responsibility. To this Bratcher provides his thesis:

“When we make claims about not voting as a result of it being a supposedly privileged act, we are drawing from all sorts of societal and cultural ideas unconsciously embedded within us and we rarely recognize it.”

In the spirit of illumination he then proceeds to identify four categories of assumption: 1.) the assumed qualitative value of ‘privileged acts’ (i.e. privileged acts are lesser to unprivileged acts"), 2.) the assumed utility in political participation, 3.) the assumption that voting is a selfless act (and therefore not voting is selfish), and 4.) the assumption that the needs we know outweigh the needs we don’t.

If Bratcher’s above statement is a defensive thesis for his position, let me try and do my best to briefly provide an offensive definition for him.1 He isn’t the problem, those of you who regard voting as the highest act of political participation are. The privilege doesn’t lie in the conscious decision to abstain. Instead the privileged ground, assuming the language of privilege is the correct one to use, is to take for granted that your highest political duty, your greatest act of participation, the most difference you can make, is to vote. If I can extend he argument a bit further, Bratcher is saying you can do better.

Problem of Privilege

I’m thankful that Bratcher tackles privilege immediately in his piece. The modern language of ‘privilege’ places us on faulty moral ground. Like setting a building on a foundation of straw, these words are now laden with moral weight they are not intended to bear. Supposed privileged acts are always cast in a negative light because they are easy when contrasted with ‘unprivileged’ ones, which are viewed as having to be made out of necessity instead of desire or choice. A privileged act is never on the same level, let alone can rise above, the unprivileged one in its quality. Neither can a privileged person. How can they when their choices, really their entire lives, are weighed in the moral balance and found wanting?

In this system, the actions of the unprivileged against the privileged are always justified since, by circumstance, they are naturally of a better moral quality. Only shaky characters will assent that the end justifies the means. Truly, truly, even a good thing (say, equality) obtained or accomplished by the wrong means (say, violence, censorship, etc.) ends in disaster. For the best of the privileged v. unprivileged crowd, their good intentions still line the road to whatever hell comes after them. That is bad enough. But in this school of language and thought, the means seem to be the end itself. Is there any other aim than to cut the legs out from under the so-called privileged, simply because they are deemed to have that undefinable thing which is irrefutably lacking in moral quality?

Not only does this language give us bad moral categories to work with, but it also makes your life meaningless. Consider the richer, more meaningful, and more accurate language of blessing/curse compared to privilege/unprivileged. What we have is the difference between a succulent Porterhouse and a tragic McDonald’s patty. In one we have a thick and expansive view of human life and experience. The other is dull, thin, and narrows life down to a single category.

What we find happening as a result of this worldview is that certain people cannot witness to the full range of human experience because of position of privilege. Can a privileged person, let us say who is white with a present mom and dad and a good education, really experience any real hardship? Can an unprivileged person who has the exact opposite background and experience, know real joy and happiness? Can the roles ever be reversed and if so, what then? Are we fatalistically bound to randomly determined materialistic circumstances?

Removed from the flat and nihilistic world of privilege, the Christian worldview reveals to us that all of life - joys, sufferings, trials, and successes - is full of meaning. We all suffer from the same affliction. Sin dwells in our hearts, flows out through our hands, and wreaks havoc on the world. We know the suffering of sin specifically in the consequences of what we do and the evil done to us. Its power is felt in general too in death, decay, and disease. That is our curse.

At the same time there is also rich blessing, spiritually and materially. Blessing is something doled out by God. Instead of the result of mere earthly circumstances, any abundance is a result of God’s grace, either specific or common. It would be a shame to buy into the current narrative that implicitly suggests that any kind of blessing, which is ultimately from God, is a really a curse. Actually that would be a great evil on our part to associate such malevolence with God.2 We would continue in wicked thought to think that God was not capable in blessing those who suffer and mourn.

But this is what the language of privilege suggests. If there is a God, then he impotent against whatever happens down here. I believe that more often than not, the people who employ such language have no space for God at all in their framework. And how could they? He offers the blessing of redemption for all people, both the privileged leeches and the unprivileged saints. He reveals sin to be a universal problem, not the specific problem of certain peoples. Since He gives gifts of blessing to people then having certain things, being born in a certain place in a certain time, and having certain opportunities cannot be inherently evil. More than all this, the call of His Kingdom is higher than the vapors of this world. It is a call for both those at the top and the bottom. There is no room for God, nor the devil, in the privilege paradigm because it is an emaciated view of the world. It does not know God and therefore forgets His adversary, thus playing right into his trick and as a result loathing what is good and forgetting that the true evil of the world is not found in so-called privilege, but in the rotting roots of all our souls.

Broken Systems

There is a great sense amongst most of us (if not all) that the political systems we find ourselves in are broken. It seems that much of the world, in one way or another, exists with some form of political anxiety. The political systems appear to be and in many ways are broken. This bleeds through in Bratcher’s piece when he writes about propaganda, our inability to know what we really need, and the fact that politics is a game played by the rich and powerful.

But you didn’t need that specifically explained to you to have the intuition that things are topsy-turvy. You already see the two party tyranny of the American system, the career politicians, and a bloated executive branch. You’ve already lived through two, consecutively, contested elections in the land of free and fair ones. You know that you’re being fed distorted information depending on your news source. Considering these things, and there are more, to participate in the machine that is chewing us up and spitting us out without any care for the people seem counter-intuitive. Actually, it feels degrading. We are the chewed and spat out as well as the spat upon - so why cast our lot with the spewers?

Along with an aversion to self-harm a conscious decision to opt out of voting, as proposed by Bratcher, is unwilling to being morally complicit in government corruption, violence, and chicanery. Here is a point in his argument where I both strongly agree and disagree with my friend. It is impossible for voting to be a moral act which stands completely above the fray, glimmering in splendor like the sun. If a person knowingly participates in a rigged and coercive election, their vote is the small lie which props up the larger one. When someone votes willingly for a tyrant they are accessories of evil. It can even be argued that someone who votes unconsciously or remains willfully ignorant of a leader or government’s malpractice is just as complicit as the previous two examples. I’d make that argument. I think Bratcher would too. In those cases, voting is a definite vice and not a virtue - a perverted prerogative.

But here, in this argument, is where friends part ways. Bratcher writes:

“All legislation is enforced by the sword. To vote for what I think is best for someone is to support holding a gun to their head while they do it.”

This is the mistake of buying into the Hobbesian lie even though we hate it. Just because the state bears a sword does not mean that it is necessarily and eternally brandished before cowering citizens. It is also not the mandatory duty for a ruler or government to exert its authority by powerful displays of force. If this were the case then we would say that tyranny, dictatorship, absolutism, despotism, and authoritarianism are the features of rule and authority, not the bug. We all know this is not the case. They are obvious perversions, both of our common understanding of authority, via the imago dei, but also of the biblical notions of authority.

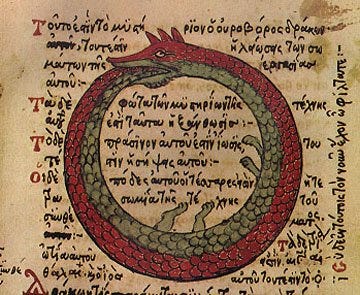

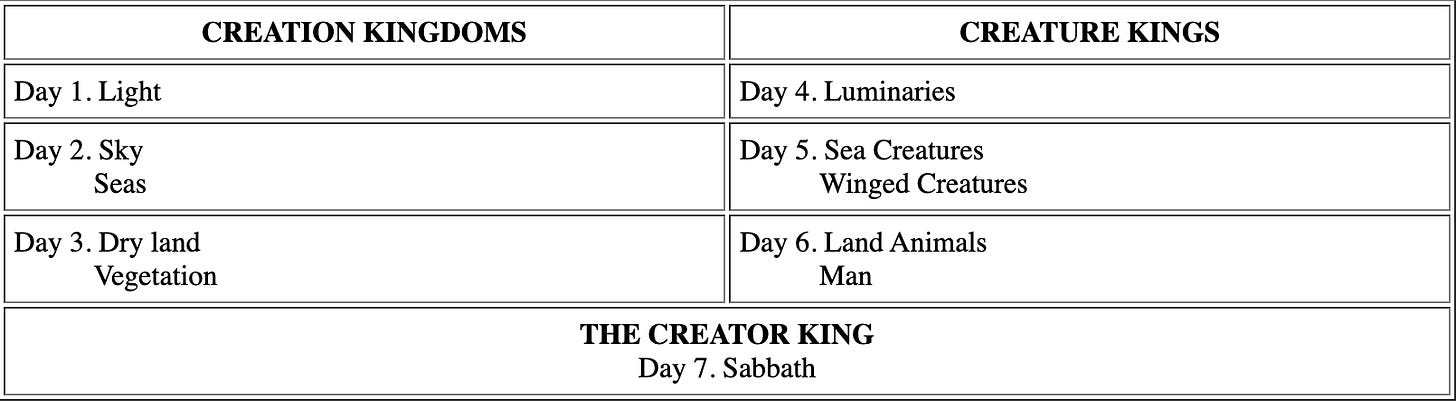

Authority and governance in the created order is present in Scripture’s first pages. The creation narrative of Genesis 1 means to show us the established order of God’s creation and that he reigns sovereignly over it.

While this is present, one only needs to read God’s command to Adam and Eve to see that rule and authority is designed into creation.3 Like everything else God has made, this structure and this command is good just as He is.

The goodness of authority does not leave the scene after the Fall, just as the goodness of God’s image is not wholly absent in postlapsarian humanity. The need for authority exists amongst God’s people, first demonstrated in Moses, then Joshua, in the Judges, also the prophets, and especially in the kings.

Now, most of Israel’s kings were abominable wretches, but this is not an issue with the office itself. As Adam was to reign as King of Eden according to godliness, so were the kings to rule according to the Law of God in the new promised land established for God’s people.4 Unlike the kings of the other nations, Israel’s kings were to be cultivators, protectors, and guards of the people and land as were Adam and Eve to be of Eden.5 The king for Israel is God’s idea, one that is thematically tied to His crowing of humanity as the chiefs of creation, the establishing them as his governors over His world, and to the future enthronement and reign of Christ the eternal King.

Paul also writes positively of governing authorities in Romans, stating that rulers are established by God for the purpose of doing good. Even in the presence of Christian persecution Paul is still able to see that all authority, by God’s common grace, is meant to image God’s supreme authority - which includes judgement against evil.

Authority is a thing derived from God, not only of His decree, but also from His character. Its end is his glorification. We image God rightly through proper usage of whatever authority, and power, is given to us. Even the sword in and of itself is not a tool of pure malice. If that were so Christ would not bear one when He returns, a day Caleb nor I can hardly wait for!

All of this is not to say that authority and power go awry. Regrettably they often do this side of glory. That is the key observation for my friend and people like Hauerwas and Ellul. Get enough sinful folks together and give them some authority, especially authority that in unchecked, someday they’ll abuse it and the people they govern. Even worse is when the Church gets a taste of the seductive draught of social and political power. Particularly in the American Church, this has gone largely unexamined, making the position on authority and power that Bratcher is making so agreeable. Believe me, I’ve dabbled. That’s where a naturally semi-antiauthoritarian personality, a childhood filled with punk music, and reading political theology will eventually lead.

But I cannot not, no matter how much I want to, negate the fact that authority is a natural and God-ordained reality. Yes, it goes wrong as often as milk goes bad. Yes, it has been the way in which perpetrators have gotten away with heinous acts. Yes, it feels great to not care because you don’t have a dog in the fight. Yes, it may even be right in certain times and places to actively abstain from the political/voting process. But it isn’t universally so.

My favorite part of Bratcher’s piece is that it is grounded like a mighty oak. He knows that in the here and now, most of politics is not in service of the people, is done by the might of the sword alone, and is for the service of the elite at the expense of the commoners. I am willing to assume that we agree on the current state of politics. I’ll let him and you know this, I’ve actually abstained from voting for President in the last two elections for most of the reasons he identifies in his piece. His view is rooted firmly in the present, and we must posit our views in the time we have been given.

However, in the general, I graciously disagree. If governments and rulers can at their best image the good God Almighty, then we cannot say that at all times, everywhere, all laws are implemented, enacted, and brought to bear on the people by a crushing, dehumanizing, and godless force. Likewise we cannot say that there are no absolute goods in which we can vote for. My home state lamentably voted to legalize abortion after the fall of Roe v. Wade. Surely that is but one example of a moral absolute that is best for all life and society in which we can put our name to?

Politics and our place in it is an unavoidable human reality. Again, and I will discuss this below, our participation must be more than a vote. But voting is still part of our vital participation in the system that affects you and me. Systems may be broken or eroding, but it takes dedicated and informed participators within the political processes themselves to some day fix what is broken or sure up the craggy cliffs of political society. My disagreement with Bratcher in this area is important, but not titanic. In considering our time, here and now, he challenges the preconceptions and de facto positions many of us hold or have held. Things often go wrong in governments like they do in schools, families, and in our hearts. But God has given us governance and it would be a shame to throw the baby out with the bathwater, or worse, let the child sink to the bottom of the tub.

Participation Reimagined

That being said, Bratcher has his finger on the pulse of our political imagination and his report is that it is dying. He’s right. There is no such thing as political abstinence and if we are to think that voting is the chief end and greatest opportunity to be an engaged citizenry, then we’re desperately wrong. Voting is our widow’s mite. However, unlike her we have enough political capital to give a hundredfold, but we waste it away.

Being members of Christ’s Kingdom, we must know that as Christians we are an inherently political people, but just not as you first imagine. The fact that Christ is Lord over our hearts, over His Church, and over all creation should really cause us to call into question our earthly actions and loyalties. Christ and His Kingdom should force us to reorder the hierarchy of our political imaginations. We must rethink what it means to be political participants. We need to broaden the scope of what it means for us to participate in politics. And, in broadening that scope, I’m convinced that means having a tighter focus.

Firstly is the most obvious and most blessedly harped upon theme I find in my little corner of Substackdom, and that is the importance of localism. Our word politics derives from the Greek polis, meaning city, and politika, meaning the affairs of the city. Politics then, includes all the goings-on where we live. The elections, procedures, and systems are not the bearers of all political weight and meaning that we’ve been programmed to believe they are. Where you spend your money is political. Where you got to school is a political act. How you invest your time, talents, and efforts is also political in nature. Your daily life is far more politically valuable than you may realize. Truly, it carries more weight. You do these things infinitely more times than your annual act of voting. And, your activity undergirds the value of your vote. Being involved in the affairs of your community adds more weight to your voting voice. The more involved you are throughout your community, the more you’re worth listening to.

Our political action must be more than just voting. Not only have we been duped into believing that voting is our chief political virtue, but we’ve also bought the bill of goods which says that our vote, in the biggest election, is the most valuable. In that way we’re all monarchists. However, you live and work and die far away from the ivory corridors of power. You do all those things in your town, county, and state though. You have more immediate knowledge and an instinctive understanding of the issues facing where you live than you do about foreign policy. Your vote certainly matters at your local and state levels than it does at the national one. If you focus local, then you rob the big churning wheels of bureaucracy of the satisfaction of dominating your life.

Second, consider your church as the center of your political activity. Not only is truer political participation local, but it includes all our actions outside the systems put in place. If where you spend your money and go to school is political, then where you worship is political - meaning it does, or at least should, act as an indicator of belief and identity. If we think as our local churches as the center of our political (our city/local/sociable) lives, then we will begin to see and live according to the reality that we are small and tiny outposts of the inevitable culmination of God’s Kingdom. The Church then begins to be the more clearly obvious alternative to the ways of the world.6 Placing your church at the center of your life is a radical act, especially since for most people their church is at the worst their self-serving buffet of religious/emotional consumption. At best it is often a second or third tier association. Imagine the impressive example set if we, believing to be one with God in Christ, were to then live and conduct our lives, not just morally but also socially, in such a manner to where our local bodies were the centers of our social and political orbit?

In this vein I’d recommend The Civitas Podcast to you all. It is a fantastic and interesting resource around this topic and discusses the idea of Ecclesiocentrism. The hosts, Dr. Peter Leithart and Dr. James Wood interview a variety of Christians from different traditions on this matter and political theology at large. I’ve found it to be very thought-provoking and know you will too.

Conclusion

So, is not voting a privilege? I guess you could say that.

But so is voting. And, so is being an active citizen in your community and for its own sake. I assume that like my friend, at the end of the day the fundamental question at hand is a boring one. As creatures we are naturally limited beings. It would be a great benefit to us if we understood our limits, both in the sense that there is an end to our capabilities and that we are not restricted to just punching an electoral ticket. We can and should do better. That takes a great amount reimagining, but that is work more worthwhile than fussing over the next head of state.

I will again say, I thoroughly enjoyed and benefited from C. Wayne Bratcher’s piece. It encouraged me. It continued to challenge me personally. His writing also allowed me to try and more formally construct thoughts I’ve been having for awhile in order to critique the areas where we disagree. This is but a tiny piece in the larger conversation surrounding our post-liberal political age and our place as Christ’s Church in it. Though we disagree we are of one Lord, one faith, and one baptism. Without disagreement we will find it difficult to strive against the challenges of our time. Iron must sharpen iron. I pray that this exercise has been such an exercise and hope it is the first of many.

Which I’m sure will send a chill down the spine of his Anabaptist instincts!

Matthew 7:9-11;

Genesis 1:28, 2:15.

Deuteronomy 17:14-20.

Important to note that in 1 Samuel 8 the mistake of Israel’s elders is not asking for a king, but asking for a king like all the other nations had instead of the one God would provide. Their desire was that “we shall be like all the other nations, with a king to lead us and to go out before us and fight our battles.” (v.20) who would subject them under his thumb instead of leading them in godliness and holy flourishing (vv.10-18).

I mean this holistically, beginning with the ordinary means of grace (Word, prayer, Lord’s Supper, Baptism). These shape our personal and communal lives and are the foundation of a church’s inner life and outer ministry, thus setting us apart from the world and creating a new people and thus a new community that is clearly differentiated from the ways of the world.

Elijah, glad to see your name pop up in my inbox again. Keep up the good work brother.

As someone who moved to Oregon as an adult, I found this piece to be really encouraging in light of the woeful political scene here. I especially agree with your emphasis on participating in the local community as more effective political involvement than voting.

For example, my younger brothers work at a local non-profit organization in town (aimed at helping disadvantaged youth get into meaningful trades), and my brothers’ attitudes to their work have earned the respect of their bosses and peers. The very politically left-leaning founder of the non-profit even chose my conservative Christian brother to represent the organization in a Q and A session with one of Oregon’s state senators, which I think perfectly illustrates your point.